Who is Ferd Hoefner?

/Local Food Champion Wins 2018 James Beard Leadership Award

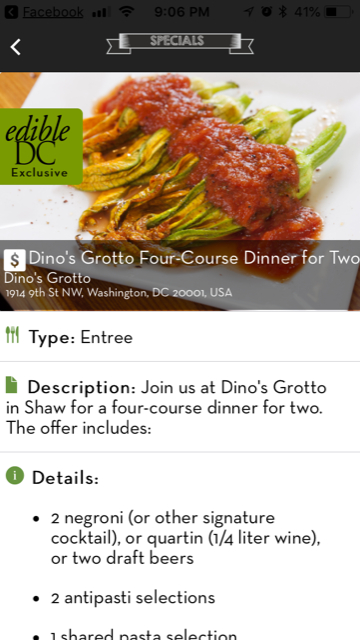

Interview by Reana Kovalcik, photography by Space Division Photography

Ferd hoefner in his takoma park garden.

With consumer demand for organic, locally grown, pasture-raised, good-feeling, good-for-you food at an all-time high, why is it that most Americans still understand so little about the policy aspect of our food system? Perhaps one reason is that policy heavy-hitters like Senior Strategic Advisor for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC) Ferd Hoefner eschew attention, craving a good key-lime pie more than they’re likely to ever crave the limelight.

Thrust into the world of celebrity chefs and “foodies” following his recent receipt of a James Beard Leadership Award, Ferd Hoefner is one reluctant food and farm hero whose name everyone should know.

For roughly 40 years, Ferd Hoefner has been at the forefront of the sustainable food and farms movement. Among agricultural policy wonks, Hoefner is a hall-of-famer who can always be counted on to have the answer to questions about the Farm Bill (he’s been working on them since the 1970s) or to explain arcane rules and regulations. DC ag journalists have him on speed dial, as do many senior congressional and administrative staff. Outside expert circles, however, his name is rarely uttered—until now.

You’ve helmed the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC) in one way or another for the last 30 years. If you had to give a freshman Member of Congress a quick elevator speech about what NSAC does, what would you say?

NSAC represents farmers who are interested in protecting the land and the legacy of family farms in this country. We do that largely through our member organizations, who work at the local and state level and interface directly with farmers and communities on the ground. NSAC bands them all together at the national level, and from our position here in DC we serve as vehicle through which our members, and all the farmers and other stakeholders they represent, can weigh in on pressing policy issues that affect their lives.

Why should the average American who isn’t a farmer care about this work?

Family farms are the bedrock that agriculture was established on in this country over a century ago, but consolidation is happening really rapidly. Some folks that favor the rise of the mega-farm will try to tell you that larger-scale farming means more economies of scale, and cheaper, better food—but that’s not true. The consolidation that’s happening isn’t so that corporate agribusinesses can make your food cheaper, it’s to increase economic returns and the ability to control land for the ownership class.

The big thing going on right now in the world of ag policy is that it’s a Farm Bill year. Explain to readers what that is in a nutshell.

The Farm Bill is the primary, but not only, federal legislation related to both farm policy and food policy. It’s particularly important because it’s so big and covers so much—from food stamps to forestry. It’s also important because [its renewal] happens routinely every five or so years, and that means there’s more democratic process and opportunities for the public to weigh in and try to move the legislation in a more progressive direction. The current Farm Bill expires on September 30, 2018, so it’s an incredibly important time to be contacting your Congress members.

So the Farm Bill isn’t just about farmers then?

It’s certainly important for farmers, but not just farmers, no. This bill affects what we eat, how we eat and who has access to that food. It’s incredibly important to every American who eats—so that’s all of us.

Reana KOvalcik and Ferd hoefner spend time with Little Nettie, Ferd's chicken.

Let’s talk a bit about you. You didn’t grow up on a farm, so how did a boy from Long Island come to find his farming roots in Washington, DC?

Right. I didn’t grow up on a farm and had limited farm experience with agriculture before coming to DC. I had come out of the peace movement and was off to college when the world food crisis was in full swing, so as an academic and an activist I became very involved and interested in that.

In the late 1970s, I was just dabbling in domestic agricultural issues, but then the famous 1979 Tractorcade happened. Farmers came on their tractors to DC to demand more support from Congress, and they ended up staying out on the mall for months! That was enough to get the organization I’d been working for, the Inter-Religious Task Force on U.S. Food Policy, to switch to more of an emphasis on domestic policy and I was asked to be part of that effort. I was learning by doing because I was immediately thrown in. It was trial by fire, and 40 years later I’m still at it.

DC has changed a lot in the 40 years that you’ve been working here. In fact, the old bakery where you used to work, Heller’s, is now a very posh restaurant and café—Ellē. How do you perceive the cultural shifts around food that the city has undergone?

When I came to DC, I was interning on Capitol Hill, but I also needed to pay the rent. So I started working at Heller’s Bakery on Mt. Pleasant Street. I’d start very early in the morning, around 4:30am, help bring the donuts and things out from the back bakery, clean the floors, etc. I’d stay through the opening rush, until around 8am, because when it opened there were always folks waiting in line at the door. Then I’d dust the flour off my clothes and head for Capitol Hill!

I haven’t seen the space since it became Ellē, but it’s cool that something is there that retains some of the flavor. What I miss in this city is the real bakeries, though. Heller’s was one of the last ones in DC. There are the various chains and there are newer places that just sell muffins and scones and things, but there aren’t really full-service bakeries around anymore.

OK, let’s come back to the present. You’ve been leading this work for over 40 years, you just won a James Beard Leadership Award, why don’t most people know who you are?

One of the not-so-hidden secrets of being an effective advocate is making sure that the attention focuses on the elected officials, who you’re hopefully convincing to champion your causes. We want the attention on those champions and on the programs themselves, that’s better for the movement.

Maybe the more pertinent question, then, is: Everybody eats, so why do so few people know anything about “food policy”?

People are interested; it’s just a complex system. The policy levers that affect it are complicated and arcane, so it takes a certain amount of hardcore interest. It’s one of the difficult things about the advocacy job, trying to communicate why a particular policy or proposal is something the general public should care about.

There are a few programs that should very understandable to folks who care about their food but aren’t wonks like me, though—like the Farmers Market and Local Food Promotion Program (FMLFPP). That’s one that NSAC helped to develop and shepherds to this day. The name of the program is a bit of an obstacle, but the benefits are pretty clear and there’s no shortage of folks interested.

Since this is for Edible DC, let me ask a question about eating. What was your favorite dish growing up?

Growing up, if you asked my family they’d cite one of two things: lentil soup, which I’m not sure my siblings appreciated, or we also had a tradition growing up that on your birthday you could make a request for dinner. I usually requested Rouladen, a cut of beef that’s prepared by rolling it around vegetables and pickles. It’s a German specialty.

Last thing: I can’t let you leave without asking about the infamous “Hoefner Food Pyramid.”

Hah! Well, I didn’t brand that, just to be clear. I just have a fondness for beer, bourbon and potatoes is all. Beer and bourbon are part of any complete diet, firstly. I also have a fondness for potatoes, despite the fact that potatoes are routinely trashed by nutritionists and foodies. I like ’em, and that’s all I have to say.

Reana Kovalcik is the associate director for communications and development with the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, as well as a member of the Slow Food USA National Policy Committee and vice chair of the Slow Food DC board. Despite being a city girl her whole life, Reana has always been interested in good food, sustainable agriculture and protecting the natural environment.