Craft Distilling: America’s “Re-revolution”

/by Aaron Tidman, special to Edible DC

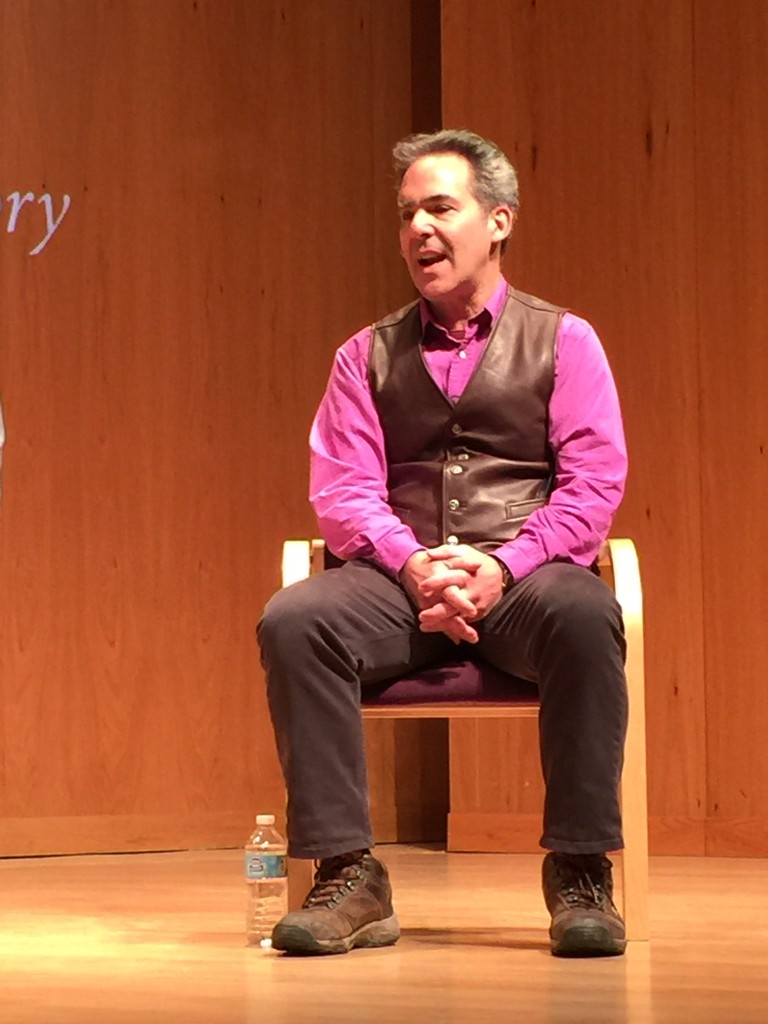

Three experts on the craft distilling movement joined forces recently at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History at a new installment of the museum’s “After Hours” series, which focuses on the history of food and drink in America. In a lively discussion about “The Craft Distilling (Re) Revolution” in the United States, the panelists – Derek Brown, a James Beard Award-nominated mixologist and owner of DC bars Mockingbird Hill, Eat the Rich, and Southern Efficiency; Michael Lowe, co-owner and distiller at New Columbia Distillers; and James Rodewald, noted journalist and author of American Spirit: An Exploration of the Craft Distilling Revolution – examined the expansion of craft distillers in recent years and the interest from consumers that has fueled the movement.

“We are a nation of drinkers and we always have been,” said mixologist Brown, noting that distilling has been an important part of our country’s past, primarily for practical purposes. Not only was drinking water often contaminated and therefore not safe for consumption in early America — meaning that men, women, and children drank alcoholic beverages routinely, mostly in the form of beer or cider — but the “economy of the farm” meant that it was more practical and profitable for farmers to distill their extra grain instead of hauling it to town.

While the number of distilleries in the U.S. has grown from approximately 70 to 729 in under 10 years, author James Rodewald pointed out that only 17 of those distilleries produce more than 50,000 proof gallons per year, so the apparent growth in output is deceptive. There is also actually no legal definition of “craft”, allowing any distiller to use the term in their labeling, an issue that concerns Rodewald “because we like things that are made by people we can meet and talk to, and we want to support local distillers and farmers.”

Brown considers the definition of “craft” to be somewhat spiritual (pun intended), saying that “craft” spirits are really about “going to the [distiller], being able to experience it,” having pride in your region, and knowing that your spirit was made with “a little bit of hands-on” love.

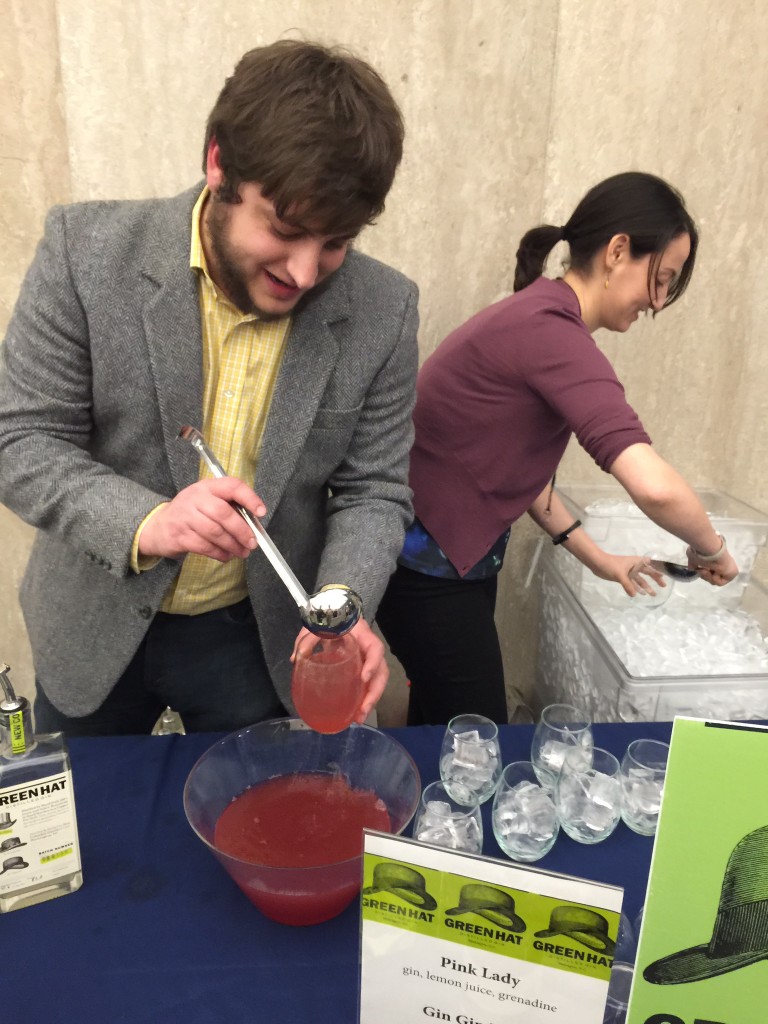

Historically, liquors were available in parts of the country where the agricultural products from which they were distilled were most commonly grown, meaning that certain regions might be known for spirits made from corn, rye, apples, and so forth. Today, these agricultural products are available nationwide, but local spirits are still prized. Michael Lowe’s own Green Hat Gin, for example, is distilled, mashed, fermented, and bottled in northeast D.C. from wheat grown in the northern neck of Virginia, giving the spirit a true local flavor.

While all the panelists agreed that Prohibition left a mighty scar on craft distilling in the U.S., damaging the structure and institutional knowledge of the distilling industry, Lowe and Brown pointed out that Prohibition also preserved the legacy of classic cocktails and modernized cocktail culture by allowing women to drink with men in the speakeasies. This increase in the drinking population created an opportunity for distillers; according to Lowe, in 1923, there were 2000 stills and speakeasies busted in Washington, D.C. that year alone.

Noting that “people consider their spirit their identity,” Brown postulated that the choice of spirits is often the result of a marketing campaign that is influencing consumer choice, asking “Do we really need a bubblegum-flavored vodka or a cinnamon-flavored whiskey?” Early in the 19th century, liquor was not sold in specially labeled bottles, but, rather, in plain jugs. Today’s marketing techniques are designed to lead consumers to a specific conclusion: for example, many whiskeys are labeled in such a way as to suggest that they were distilled in the state in which they were bottled, but unless the label actually says, “Distilled In Kentucky,” then it probably wasn’t.

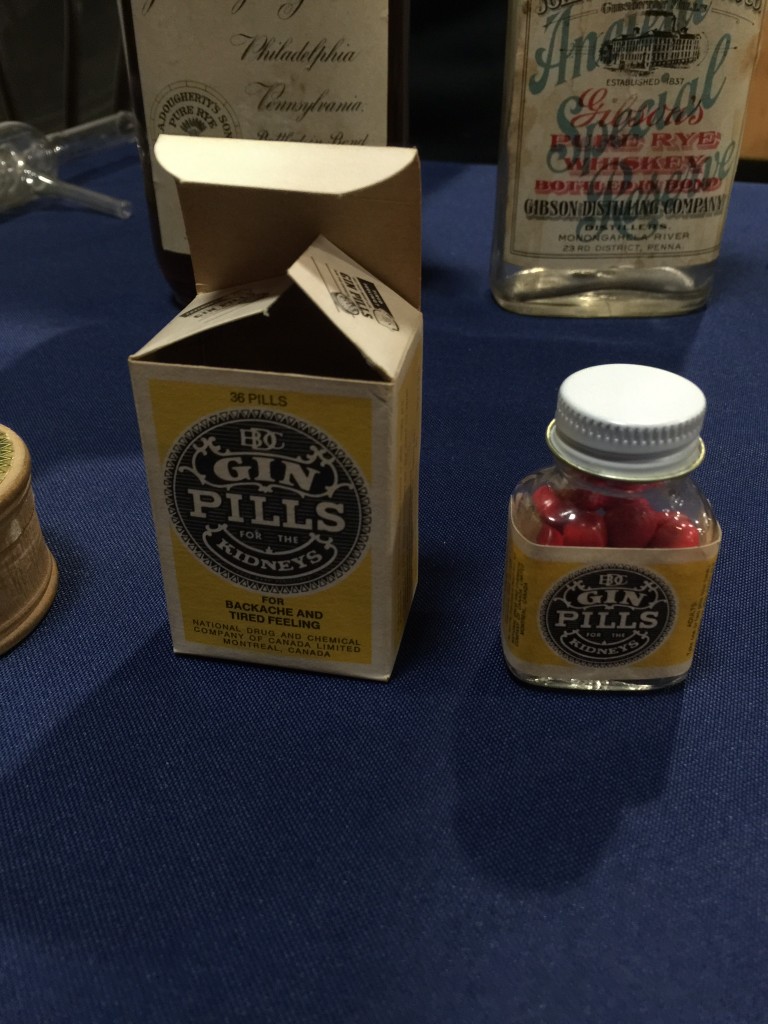

Following this informative discussion, audience members had a chance to sample cocktails featuring Green Hat Gin and snacks from Chef William Bednar, Executive Chef of the National Museum of American History. The museum also displayed several objects from its food history exhibit, including one of Lucille Ball’s cocktail hats, an old home pot still, bottles of whiskey, and “gin pills” that doctors prescribed patients in the early 1900’s.

You can learn more about the American History (After Hours) events here.